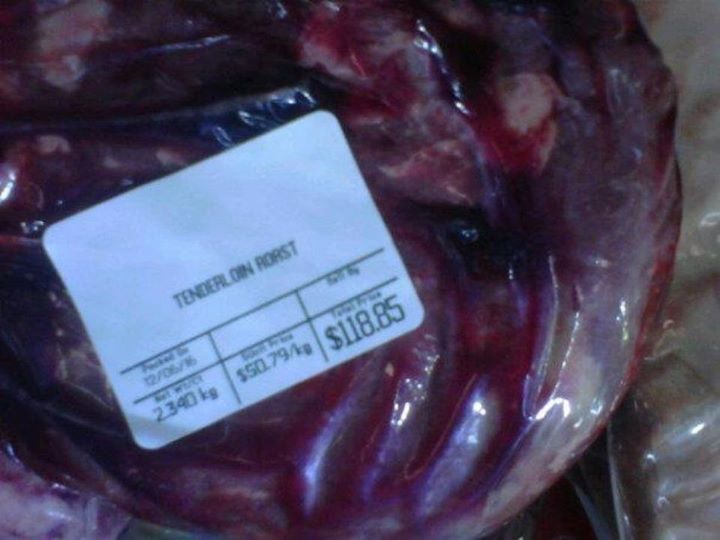

At first glance, the image of a tenderloin roast frozen beneath ripples of plastic wrap, a hardened ball of flesh, fat, and blood, may not seem like a picture to pause over. What kind of story could one more glimpse of the grocery store graveyard of meat have to tell us? Is this frost-bitten maroon lump the opening scene for an exposé of industrial abbatoirs or inhumane agribusiness? Perhaps it could be. But photographed in a store in Pond Inlet, Nunavut and posted online by Israel Mablick Sr. as part of Feeding My Family movement, the 2.34 kilograms of tenderloin roast and its price of $118.85 was meant to bring another story into focus.

In 2010, the Government of Canada replaced its Food Mail Program with the Nutrition North Program that was touted as reducing the cost of distributing what bureaucrats deemed healthy “perishable” foods to remote northern communities. Despite government promises, food prices across Nunavut soared rather than decreased. In his report on his May 2012 visit to Canada, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food expressed concern “that the retail subsidy is not being fully passed on to the consumer and that in the absence of adequate monitoring by those it is intended to benefit, the programme is not achieving its desired outcome.” These events prompted Leessee Papatsie, a resident of Iqaluit, to organize a demonstration and develop a Facebook group called “Feeding My Family” to unite people across the North in a call for justice. To garner the attention of both Indigenous peoples and settler Canadians alike, the movement urges viewers to photograph prices in their local stores in order to re-frame the quotidian scene of the grocery as a spectacle of extraordinary disparity between northern and southern Canada.

While the “Feeding My Family” Campaign is most urgently about Nutrition North, it is also about a much longer story that reaches back, at the very least, to the mid-century intensive colonization of the Inuit. Under pressure by Cold War American expansion in the Arctic, the Canadian government dispatched the welfare state northwards, moving

Inuit into “settlements” with inadequate housing and infrastructure and killing their sled dogs, and with them, Inuit mobility and self-reliance upon traditional hunting and foodways. While the rest of Canada received family allowances direct to their mailboxes, Inuit allowances were given to HBC post owners who were then entrusted to mete out government-approved provisions. In the interests of preservation, the hunting of caribou and other animals became regulated by colonial agents, further altering Inuit’s ability to live on country foods as they had done for centuries. Viewed from this lens, the frost-bitten tenderloin roast languishing in an industrial freezer in Pond Inlet becomes a parable about the blindnesses of colonial paternalism. How does a $118 roast shipped from a southern meatpacker, ostensibly subsidized as a healthy “perishable,” compare to the settler state’s making-perish of a way of life in which Inuit were able to hunt and to eat the bounty of their land?

Viewed in this light, the Feeding My Family Campaign is about the right to Inuit sovereignty over their land and bodies. It is also a call to see the current restriction of Inuit rights as fundamentally related to the privileges that non-Indigenous Canadians take for granted at their supermarkets and their homes in the south.

Pauline Wakeham - Associate Professor, Western University

pwakeham@uwo.ca